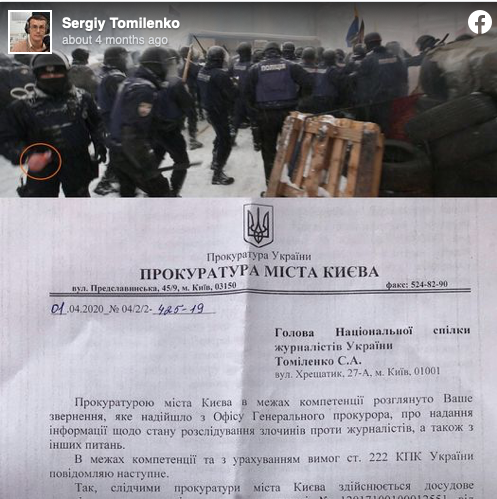

In Ukraine there is an unacceptably high level of physical aggression and violence against journalists and this is one of the greatest threats to freedom of speech. There are attacks by politicians, dishonest local government officials, businessmen and ordinary citizens. For example, during the coronavirus pandemic, there were individuals who did not want journalists to record and publicize violations of government orders. As a result, many cases of brutal beatings of journalists and obstruction of their work were recorded.” These are the words of the President of the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine Sergey Tomilenko, who adds: “we are obliged to say that a dangerous stereotype of aggressive behaviour towards the non-compliant journalist is being formed in society: a journalist can be beaten up, have his or her TV camera or camera destroyed and the person who does it can be sure that he or she will not be punished. This stereotype is reinforced by the fact that during intense clashes and events, police representatives use physical violence against journalists. Importantly, these acts of the police officers usually go unpunished and even without anyone even bothering to investigate the complaints; the aggressors are not punished in a proper manner; this impunity becomes systemic; the journalist feels defenseless and, in the end, has to be very brave to continue working.” You can read here in a short piece we published last May, from the eloquent title “Enemies of the Press 2020” how Sergei Tomilenko outlines the current situation in the field of journalism, freedom of speech, independence of the press, and the difficulties journalists face in their daily life and work. Dimitris Triantaphyllides spoke with him.

#WorldPressFreedomDay2020 Physical aggression, impunity, efforts to change media laws and the economic crisis are among the main enemies of press freedom in Ukraine https://t.co/JnCP90xF3k

— Sergiy Tomilenko (@Stommedia) May 3, 2020

How many of our colleagues have suffered attacks of physical violence during the last few years? How many of these cases have been examined in the country’s courts? What were the judges’ decisions?

A systematic record of cases of violence against journalists has been kept by the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine since the end of 2013, when the Dignity Revolution began in the country. At that time in Ukraine we had the world-famous Euro-Maidan events: in many cities of our country, citizens held mass protests against the policies of then President Viktor Yanukovych. All over the country we had fierce clashes between the protesting citizens and representatives of the forces of order loyal to the then power. Journalists were at the forefront of reporting on those tumultuous events.

In that period, from late 2013 to early 2014, 271 cases of severe beatings of journalists in the country and international media were recorded. One of our colleagues, Vyacheslav Veremi, while performing his duties, was murdered in the centre of our capital. The investigation of the case took a long time and only under pressure from public opinion was the case brought to court, resulting in the conviction of the guilty party.

And while the murder of the well-known Ukrainian journalist Georgi Gongadze in 2000, after a trial that lasted many months, finally led to a verdict of guilty, the murders of other journalists, such as the 2016 murder of the well-known Ukrainian journalist, Mr. Gogadze, were not, Belarusian and Russian journalist Pavel Sheremetev and in 2019 of our well-known investigative journalism colleague from Cherkassy, Vadim Komarov, regardless of the great publicity in Ukraine and internationally, are currently under investigation.

Throughout 2019, we have been raising the issue of investigating these murders and other crimes against journalists.

There are laws in your country that protect journalists. If so, how much do the institutions of power observe them?

In the Criminal Code of Ukraine, there are articles protecting journalists. They provide for penalties for attacks on journalists, for murder, for obstructing the exercise of the profession, for hostage-taking. Too often, however, we are forced to point out that good laws remain on paper; in everyday life they are not applied as they should be. Our basic request to the police and the courts is that they create mechanisms to enforce these laws.

What issues is the Committee on Freedom of Speech of the Parliament of Ukraine dealing with? What are the results of this activity?

Traditionally, the Parliamentary Committee on Freedom of Speech is chaired by a representative of the opposition. It is one of the features of democracy in Ukraine, a kind of peculiar social control. At the same time, we argue that in the parliament, which has been elected in the early elections in 2019, there have been changes in the activity of the Committee for Freedom of Speech. Now, the committee, which has always been central to parliamentary work, has lost the ability to solve media problems, to regulate the relevant sector. Today, the functioning of communication policy, including the media, the influence on them of actors outside the industry, has passed to the competence of the Committee on Humanitarian and Information Policy, which is controlled by the authorities.

The current Committee on Freedom of Speech, which includes only five MPs, is responsible for protecting against violence and obstruction of the journalistic profession. At the same time, this committee has organised parliamentary hearings on the issues of protecting journalists from attacks; it examines all cases of violence against journalists, regardless of the political position of the media. The position of the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine is that the transfer of part of the powers of the parliamentary committee on freedom of speech to the committee on humanitarian and information policies actually weakens its position on the protection of freedom of speech and, consequently, the protection of the media.

Already today we see that the first major initiative of the parliamentary committee on humanitarian and communication policy issues is the drafting of the bill to end harsh measures to regulate the media landscape, for new, additional, powers of the national regulatory authority, which is the National Broadcasting Council. It is obvious that the focus is not on supporting, but on influencing the media.

What measures did your government take to support the media during the pandemic?

The Ukrainian government was not in a hurry to take measures to support the media. Unfortunately, even at the level of the state leadership, we do not expect recognition of the importance of the role of the media, that journalists in pandemic conditions, like doctors, policemen and some other specialties, were among the most important forces of resistance to the spread of the virus. But it was the journalists who reached out to the broader sections of society to inform them about the coronavirus, it was they who explained to the population and warned them of the consequences of the pandemic.

It was the journalists who raised the issue of their tax exemptions, as was the case with businessmen. At the moment, however, we have not been able to convince high-ranking officials and parliamentarians. It is possible that, due to the economic crisis, it will be necessary to allocate resources to deal with the natural disasters that Ukraine has faced this year. At the moment, the only step the government has taken in relaxing the quarantine has been to allow press distribution points to operate, which is generating some small revenues.

The National Union of Journalists of Ukraine is in consultation with publishers. We have agreed on the form of state subsidies to regional and local media for the information they provided on the pandemic in Ukraine. New legislation should provide for the possibility for the authorities to publish paid announcements on regional and local radio, television, newspapers and magazines, announcements informing the public about the fight against coronavirus. In this way, the state should allocate resources to the information campaign and make up for the losses of the Ukrainian media from the advertising market. As an argument we have similar practices adopted in the countries of the European Union, the USA, Australia, New Zealand.

In the eastern regions of the country, a war has been going on for several years with the militants of the separatist movement and Russian mercenaries. What is it like to work there as a journalist? What are the dangers he faces?

Since the end of the Second World War Ukraine has lived in peace. In 2014 Russia, which we always considered a brotherly neighbour, annexed Crimea. Since 2014 the war was now a harsh reality for our country: part of the territories of the two industrial regions, Donetsk and Lugansk, with the strong help of the Russian military, is controlled by the separatist movement.

Particularly difficult years for us were 2014 and 2015. We had military operations, during which many Ukrainian volunteers and soldiers were killed. In those days our colleague, photojournalist of the newspaper ‘Today’ Sergei Nikolaye was also killed.

In the occupied territories, the buildings of many regional and local newspapers have been destroyed, many journalists and newspaper executives have been arrested, received threats, wanted to force them to work for the separatist movements. Thus, the premises of major newspapers such as ‘Donbas’, ‘Donetsina’, local newspapers in Torez, Lugansk, Gorlovka were destroyed. At gunpoint they threw out of the building of the newspaper “Donbas” the editorial director and chairman of the regional organization of journalists in the region Aleksandr Breeze. Fortunately, he miraculously escaped arrest and managed to flee into the Ukrainian-controlled region.

However, the Lugansk journalist, Maria Varfolomeyeva, remained a prisoner for several months and was released during the prisoner exchange between Ukraine and the self-proclaimed pseudo-democracy of Lugansk-Donetsk. It was the Radio Liberty journalist Stanislav Aseyev who was the one who was held captive the longest. He was illegally held in prison on trumped-up charges of terrorist activity. He was not allowed to meet with lawyers, representatives of international missions, so it was very difficult to help him.

Nevertheless, we held solidarity events for the imprisoned journalist, calling on the Ukrainian authorities and international public opinion to put pressure on the separatists, demanding the release of Stanislav Aseyev. He was released during the prisoner exchange.

At present, we have no information about captured journalists in Donbass. In the meantime, journalists in the Ukrainian-controlled areas cannot work in the occupied areas of Donbass.

The Ukrainian media are only able to report on events in the occupied territories through contacts with relatives, acquaintances living in these areas and through social networking sites. We do not have direct access to the events in order to objectively convey our information to readers, listeners and viewers.

An important event of 2014 was the mass emigration from the occupied regions of Donbas of hundreds of journalists from Donbas and Lugansk, who did not want to serve the ideas of the separatists, to work for their propaganda media. It was very difficult for them to be deprived of their beloved work, their way of life, to leave their homes, taking with them the bare necessities, and to start life again in an unknown town or village. The forced refugees from Donbass repeated the route already taken by the journalists from Russian-occupied Crimea. To the credit of these refugees, all of them tried as far as possible to remain in the profession.

The National Union of Journalists of Ukraine since 2014, when these forcibly displaced journalists appeared, has tried to stand by them, to help them in their search for work throughout Ukraine, organized seminars of psychological and social support, helped them to the extent of its power to reorganize their daily lives. Local journalists, as well as ordinary residents who were not involved in journalism, also supported the displaced persons. Today, the Danesque journalist Lina Kuszcz is the elected First Vice-President of the National Union of Journalists and is very active in working with the journalists who were forcibly displaced.

However, even today, there are still many acute issues that require solutions. First and foremost is the issue of housing and the issue of employment. Both of these issues were exacerbated during the pandemic. However, we dream of the return of Crimea to Ukraine, of peace in Donbass, so that journalists from these regions can work there again.

Recently, information was made public about the arrest by the Russian authorities of an amateur journalist in Crimea. How did the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine react to this? Do you have relations with colleagues in Crimea? How are things there with freedom of speech?

Of course, the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine stands in solidarity with our colleagues who, under occupation in Crimea, are trying to defend freedom of speech, the right to objective information about the events.

Today, when the majority of pro-Ukrainian journalists in the Crimean media have left and are working in the Ukrainian-controlled regions, a movement of citizen journalism has developed on the peninsula. Representatives of the Crimean Tatar people ensure the flow of news, report on events in the region, especially when we have illegal arrests of citizens, when the rights and freedoms of the inhabitants are being violated.

In international forums we constantly express our solidarity with these brave people, who are suffering under the oppression of the Russian authorities. The names of Nariman Mementeminov, Sherver Mustafaye and other colleagues who are being persecuted for their political beliefs are constantly heard at international level. They are in Russian prisons.

We hope for international support in our struggle for their release. However, we should note that we do not have the slightest possibility of influencing the situation, of defending our colleagues in direct contact with the representatives of the Russian authorities.

Similarly, we believe that it is impossible to talk about freedom of speech in Crimea today. A vivid example of the lack of freedom of speech on the peninsula was the incident with our colleague, activist of the National Union of Journalists, Nikolai Semena.

Having extensive experience in the Ukrainian and international media, a high reputation among journalists and readers for his truthful reports on life in occupied Crimea, he was banned by a Russian court decision from practising journalism. Moreover, having health problems, Nikolai Semena was deprived of the right to leave the peninsula and come to mainland Ukraine. It was only when his sentence expired that the journalist was able to come to Kiev, receive proper treatment and resume his chosen profession.

How are your relations with your Russian colleagues, both between professional associations and on a personal level? Do you hold joint events?

The annexation of Crimea and the occupation of Donbass in 2014 was a shock for Ukrainians and for Ukrainian journalism and was aired quite a lot at the international level. Then, on the initiative of the Office of the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunia Miatovic, in spring 2014 the dialogue between the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine and the Independent Media Syndicate with the Union of Journalists of Russia was launched. The dialogue was held in the OSCE framework in Vienna and was seen as a concrete form of joint reaction to the events in the recent history of Ukraine and Russia.

We should say that we managed to achieve mutual understanding with our colleagues from the then Russian Union of Journalists on the issues of security and solidarity, on the issue of condemning hate speech, propaganda and violence. As a result of this joint action by the two associations, a number of Ukrainian journalists were released from captivity in Donbass. Lawyer and activist Valery Makeyev, in his autobiographical book ‘100 days in captivity or Code 911’, notes about his captivity that the joint statement of Ukrainian and Russian journalists was decisive for his release.

Then, in the years that followed, there were changes in the views of Russian journalists. After the change of leadership in the Russian Union of Journalists and its takeover by young people who fully support the actions of the Russian leadership, we immediately saw from their actions and statements that they are not ready to come into conflict with the authorities on the issues of freedom of speech and the defence of journalists’ rights. Over time and specifically in 2017 and 2018 our dialogue stopped. Of course, we meet with them at various events and debates. Our contacts, as a rule, are limited to appeals to our Russian colleagues, with which we try to draw the attention of the Russian Union of Journalists to the problems of persecution of Ukrainian journalists in the occupied Donbass regions and in the annexed Crimea.

In particular, these appeals also referred to the journalist of the Ukrainian News Agency ‘Ukrinform’, Roman Shushchenko, who was illegally arrested in Russia and sentenced on trumped-up charges to several years’ imprisonment. At the time we also drew the attention of our Russian colleagues to the case of the journalist and writer Stanislav Asseyev, the Crimean journalist Nikolai Semena, imprisoned in Donbass. But we have not seen any real reaction to all this.

The issue of the release from Russian prisons of journalists – citizens from the Crimean Tatar minority – remains topical today. However, despite our appeals to our Russian colleagues, we do not see any real reaction. For this reason we see no prospect of organising joint events, nor of joint participation in programmes and forums with our Russian colleagues.

Have you had solidarity from the side of your European colleagues?

We are grateful to our European colleagues for the support, solidarity from the European Union of Journalists, of which our National Union is a member. I, as the President of the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine, was elected a member of the Executive Committee of the European Union of Journalists, and this shows the readiness of European countries with considerable experience of democracy to support the countries of Eastern Europe, where at present there are many problems with the development of democratic institutions.

The National Union of Journalists of Ukraine cooperates with international organisations such as the UN, the European Union, the Council of Europe, the International Federation of Journalists, Reporters Without Borders. We are trying more and more actively to develop international relations with associations and organizations of press workers, not only in Europe, but also in other countries of the world. In particular, on an annual basis we exchange visits with the Chinese Association of Journalists.

Our Union has close relations with the Polish Journalists’ Association, with which we regularly hold meetings in Kazimierz Dolny, conferences with the participation of many journalists from Poland and Ukraine. At these conferences and meetings we are constantly examining issues related to the safety of journalists, the fight against misinformation, fakenews, and compliance with the rules of journalistic ethics.

What are your plans for the development of the journalists’ trade union movement in Ukraine?

Our main priority is the development of journalistic solidarity in Ukraine. Our colleagues are very often forced to work in conditions of intense polarization in society, when people are often angry, oppressed by the problems of everyday life and become very irritable in their opinions, resentful of each other’s point of view.

In the media we also see the dependence on ownership of the media, on influential politicians. We also observe that among journalists the practice of intolerance has prevailed, when journalists themselves do not accept for discussion the views of others, at the media level the debates regarding content, authors and experts are not conducted in the right way.

The older generation of journalists does not always accept as journalistic work what is done on the Internet. Sometimes professional discussions are sometimes held in a very vulgar way on social networking sites. For this reason, our aim is to unite those working in traditional media with those working online. It will then be easier for us to defend our professional rights, and then both politicians in Ukraine will have more respect for journalists and citizens will have more trust in the media.

Our role is very specific, and in particular we believe that we should help the media and journalists in the transition to the digital age. First and foremost, we try to help traditional media, in particular local newspapers, to adapt to the new conditions, to introduce digital tools in their work.

We do not have the right to limit ourselves to traditional media. It is a great challenge to keep up with the times, having as a priority the unification of Ukrainian journalists and defending them from every obstacle they encounter in the exercise of their profession.

–